For Australian energy, 2020 started precariously. The bushfires showed the vulnerability of the nation to its subsidy-induced reliance on renewable energy.

Average prices in January reached near-record levels. In addition, the market manager was forced to intervene spending over four times as much as normal — $310 million — buying services and compensating suppliers in order to stabilise the system.

In February, low demand, an influx of renewable energy, and high supplies of hydro brought about a halving of the previous month’s prices. These conditions continued in March when they were reinforced by a forced cessation of demand and ample gas supplies caused by the COVID-19 crisis.

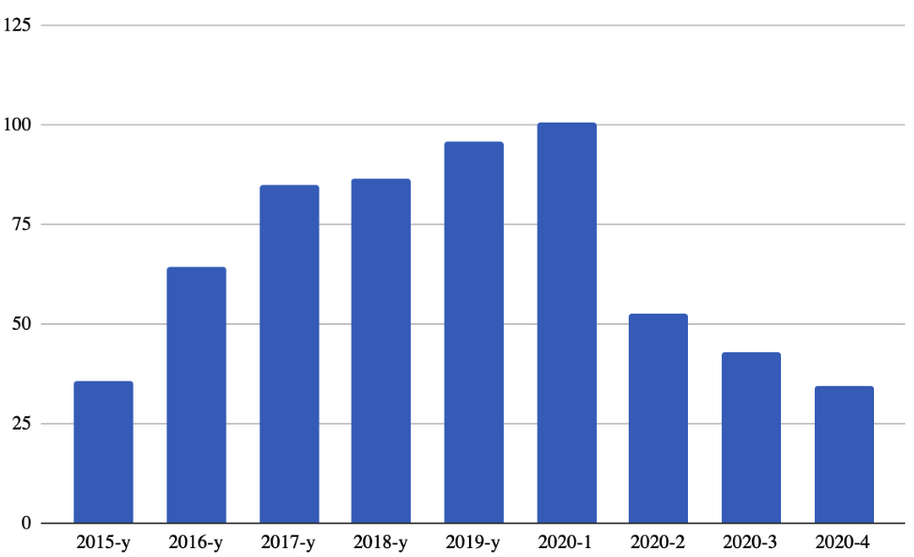

And in April prices fell to $35 per MWh. Such levels were last seen five years ago, before wind/solar subsidies caused closures of two major coal power stations, resulting in a two-and-a-half-fold increase in prices and, due to the higher share of intermittent electricity, a permanent lift in unreliability.

Price of Electricity: NEM Average ($/MWh)

Forward markets indicate that prices that were previously forecast at $75 per MWh are now at around $55 per MWh, a level that will be maintained through 2021. This trend could continue in later years if, as is constantly threatened, one of the big three aluminium smelters were to close, thereby reducing national electricity demand by five per cent.

Long term, the low prices cannot be maintained with the current wind/solar-rich generation, even if there is an-ongoing de-industrialisation. Wind and solar costs are difficult to estimate since the contracts are confidential and the headline price contains various contingencies. CSIRO estimated the cost of wind at around $50 per MWh and Bloomberg New Energy Finance at $40-74. Lazards put the cheapest wind at $52. On some estimates, large scale solar is cheaper. China, which in the March quarter of 2020 announced approved more new coal capacity than in the whole of 2019, is clearly unimpressed with such estimates.

One reason for this may be that intermittent renewables also need a firming contract which presently costs $40 per MWh but which Snowy Hydro says will fall to $25-30. Add to this, wind (but not solar) earns a discount on the average spot price because of its lesser availability during high price events (when typically, there is little wind). According to the Energy Council, wind on average received in 2018/19 24 per cent less per MWh than the average spot price in South Australia (in NSW it was only five per cent less).

A further cost is that seen in January this year when the market manager had to buy, and charge to wind farms, frequency control services (FCAS) and require backoffs, with wind farms also choosing to back off to avoid high FCAS charges.

Thus, if the spot price is $55 per MWh, a wind farm capable of a variable production cost of $50 per MWh would need $90 per MWh because of

- its earnings being discounted by, say 20 per cent, or $10 per MWh

- a hedge cost at, say, $30 per MWh

In addition, it would have other costs caused by the lack of system strength and FCAS charges.

Offsetting these penalties, wind and solar receive the renewable subsidy, which last year averaged $31.5 per MWh (about $457,000 per turbine). Forward prices have this declining to around $20 per MWh. Long term it has to fall to zero which means a wind/solar dominated system would deliver electricity with support to offset wind/solars’ intrinsic unreliability at best at $80 per MWh.

Wind and, to a lesser degree, large scale solar is now a mature technology and is likely to see cost reductions not dissimilar from those of nuclear of fossil plant.

In Australia a system dominated by coal plant, supplemented by fast start hydro and gas, can provide a highly reliable electricity supply system at around $55 per MWh. China and other developing countries would probably not be able to match this as they lack the low cost and conveniently located coal we have on the East coast. Even so, they will have nuclear/fossil fuelled electricity at far less than the $80 we can hope for from our present policy settings. The energy intensive industries are therefore likely to migrate away from Australia and other industries will see costs higher than they need, an outcome of which is a lower exchange rate and lower living standards.

The market manager, AEMO, has released a plan that indicates the network could accommodate up to 60 per cent “instantaneous penetration of wind and solar and could be adapted to accommodate 75 per cent. AEMO does not specify what the costs of this would be.

Meanwhile, renewable energy lobbyist Martijn Wilder, who the Commonwealth has appointed to head up hand-outs to renewables through the Australian Renewable Energy Agency, finds their appointee is calling for more monies to be directed into renewables as a result of coronavirus. His views are supported by the head of the Business Council who opined, “Every dollar we invest in energy, should be a dollar towards a lower carbon economy”.

Maybe we just want to be poorer than we need to be.

Alan Moran is with Regulation Economics. His latest book is Climate Change: Treaties and Policies in the Trump Era.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in